Roman Emperors Dir Constantine I

An Online Encyclopedia of Roman Emperors

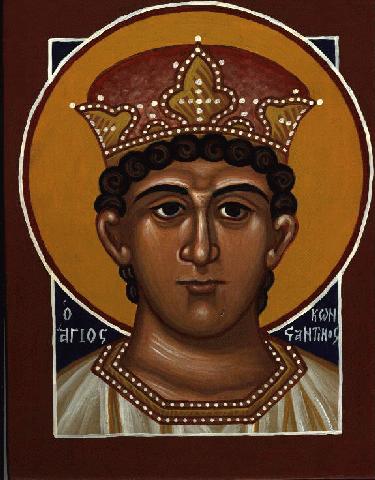

Constantine I (306 - 337 A.D.)

Michael DiMaio, Jr.

Summary and Introduction

The Emperor Constantine I was effectively the sole ruler of the Roman world between 324 and 337 A.D.; his reign was perhaps one of the most crucial of all the emperors in determining the future course of western civilization. By beginning the process of making Christianity the religious foundation of his realm, he set the religious course for the future of Europe which remains in place to this very day. Because he replaced Rome with Constantinople as the center of imperial power, he made it clear that the city of Rome was no longer the center of power and he also set the stage for the Middle Ages. His philosophical view of monarchy, largely spelled out in some of the works of Eusebius of Caesarea, became the foundation for the concept of the divine right of kings which prevailed in Europe.

Constantine's Youth and Early Reign

Flavius Valerius Constantinus,[[1]] the son of Constantius Chlorus and Helena, seems to have been born in Naissus in Serbia on 27 February ca. 272 or 273 A.D.[[2]] When his father had becomeCaesar in 293 A.D., Constantius had sent his son to the Emperor Galerius as hostage for his own good behavior; Constantine, however, returned to his dying father's side in Britain on 25 July 306. Soon after his father's death, Constantine was raised to the purple by the army. [[3]]

The period between 306 and 324, when Constantine became sole imperator, was a period of unremitting civil war.[[4]] Two sets of campaigns not only guaranteed Constantine a spot in Roman history, but also made him sole ruler of the Roman Empire. On 28 October 312 he defeated Maxentius, his opponent, at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge; in 314, 316, and 324, he repeatedly defeated his last remaining rival Licinius. Once he had overcome him, he was the undisputed ruler of the Roman world. [[5]] In passing, it is worth noting that Maxentius and Licinius were both brothers-in-law of Constantine.[[6]]

Constantine and Christianity

Of the two campaigns, however, it was the first against Maxentius which guaranteed Constantine an important place in the history of western civilization because he attributed his victory to Jesus Christ; on the evening of 27 October 312, he had seen the Chi-Rho, the sign of Christ, in the heavens outside of the city of Rome.[[7]] Starting in February, 313 with the promulgation of the so-called Edict of Milan, in which Constantine and Licinius granted Christians the freedom to practice their faith without any interference from the state, Constantine began the process of making Christianity the official state religion in place of paganism,[[8]] a process only completed in 391 during the reign of Theodosius I. [[9]] He did this by passing laws which favored Christianity. His adoption of the celestial divine sign (caeleste signum dei) in October, 312 was probably initially an act of political expediency. Although Constantine himself seems to have been sympathetic to the Christian faith as early as 312, he only converted to Christianity when he was baptized by the Arian Eusebius Bishop of Nicomedia shortly after 3 April 337.[[10]]

Because Constantine wanted to replace paganism with Christianity as the official state religion, he needed a unified faith which would serve as the religious backbone of the empire. He quickly found through his dealings with the Donatists in North Africa and the followers of Arius in the eastern portion of the empire that persuasion was not enough to forge a solid, unified faith. In an attempt to resolve the Arian controversy, he convened the first Ecumenical Council in the history of the church, which assembled for its first session at Nicaea in Bithynia during June, 325.[[11]] Although this action of the emperor was of a transitory nature in the course of ecclesiastical affairs in 325, it was the most profound event of his reign because it set a precedent that remains in place today. When either the Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox Churches have major dogmatic or disciplinary problems to resolve, they would convene an ecumenical council to settle the matters in dispute. Because of the fact that he clearly favored Christianity, the Eastern Orthodox Church considers him a saint.

Constantine's Foundation of Constantinople

In 324, after his defeat of Licinius, Constantine decided to rename Byzantium after himself and make it a governmental rival of the "Old" Rome; the renaming took place after 18 September 324 and before 326, although the actual construction started late in 324.[[12]] The emperor's building program was quite extensive and included the construction of churches and, it is said, paganism was excluded from the city.[[13]] Constantine had the city officially dedicated on 11 May 330; although the emperor said he had founded the city on orders from God, the dedication ceremonies of the city offended no one. The city itself, however, was only an imperial residence until 359 when it became the official capital of the empire.[[14]]

Although Constantine reputedly used Licinius' war chest, which he had captured there, to meet the expenses of the new construction in Constantinople,[[15]] the cost to the imperial treasury had to be extensive in light of the emperor's apparent lavishness in relation to finances. In fact, each time the emperor levied a tax on his subjects, they groaned. The sixth century Greek historian Zosimus gleefully notes that Constantine's taxes were so excessive that fathers were forced to hire out their daughters as prostitutes to pay debts.[[16]] In any case, the emperor seems to have been an easy target for the unscrupulous[[17]] .

Constantine's Death

Constantine died on 22 May 337 near Nicomedia on his way east to fight the Persians.[[18]] Constantine II, Constantius II,Constans I, Constantina, and Helen, born of his union with Fausta, survived him,[[19]] whereas Crispus, his son by Minervina,[[20]] was executed ca. 326 along with Fausta for reasons that are not clear.[[21]] After a bloody purge of members of the Royal family which may have had its roots in the religious strife between the Arian and Orthodox factions at the imperial court, the three sons of the late emperor were raised to the purple by the army on 9 September 337.[[22]]

Bibliography

Alföldi, A. The Conversion of Constantine and Pagan Rome. Oxford, 1969.

________. "On the Foundation of Constantinople: A few Notes." JRS. 37(1947): 10ff

Andreotti, R ."Licinius(Valerius Licinianus)." Dizinario epigrafico di antichitâ romane 4: 1000ff

Barnes, T.D . Constantine and Eusebius,, Cambridge, 1981.

________. "Lactantius and Constantine." J RS: 63(1973): 36ff.

________. New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine. Cambridge, 1982.

Bruun, Patrick. Constantinian Coinage of Arelate, Helsinki, 1953.

________. Roman Imperial Coinage 7: Constantine and Licinius A.D. 313-337. London, 1966.

________. Studies in Constantinian Chronology. New York, 1961.

Dagron, G. Naissance d'une capitale: Constantinople et ses institutions de 330 à 351. Paris, 1974.

De Cavalieri, P. Franchi. "Il fumerali ed il sepolchro di Constantino Magno." Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire de l'École Français de Rome 36(1916-1917): 206ff

DiMaio,Michael, Jörn Zeuge, and Natalia Zotov. "Ambiguitas Constantiniana: the Caeleste Signum Dei of Constantine the Great," Byzantion 58(1989): 333ff.

________. and Arnold,Duane. "Per Vim, Per Caedem, Per Bellum: A Study of Murder and Ecclesiastical Politics in the Year 337 A.D.." Byzantion 62(1992): 158ff.

________, Jörn Zeuge, and Jane Bethune. "The Proelium Cibalense et Proelium Campi Ardiensis: The First Civil War of Constantine I and Licinius I." AncW: 21(1990): 67ff.

________. Zonaras' Account of the Neo-Flavian Emperors, (Ph.D. diss., University of Missouri-Columbia, 1977).

________. "Zonaras Ecclesiasticus: Three Source Notes on the Epitome Historiarum." GOTR 25(1980): 77ff.

________. "Zonaras, Julian, and Philostorgios on the Death of Constantine I." GOTR 26(1981): 118ff.

Heilland, F. "Die Astronomische Deutung der Vision Kaiser Konstantins," in Sondervortrag im Zeiss-Planatarium-Jena. Jena, 1948.

Jones, A.H.M. "Constantinople." OCD.2 281.

________.. "Theodosius (2) I." OCD.2 1055.

_________. The Later Roman Empire: 284-602. Norman, 1964.

Kienast, Dietmar. Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie. Darmstadt, 1990.

Kidd, B.J. History of the Church to A.D. 461,Oxford, 1922.

Mattingly, Harold, and B.H. Warmington ."Constantine." OCD.2 280

Oberhummer, E. "Constantinopolis." RE 4: 968ff

Pohlsander, H.A. "Crispus: Brilliant Career and Tragic End." Historia. 33(1984): 99ff

________. "The Date of the Bellum Cibalense: A Reexamination." AncW 25 (1995): 89-101.

Seeck, Otto.. " Licinius (31a). RE 13: 222ff.

________.. Regesten der Kaiser und Päpste für die Jahre 311 bis 476 N. Chr.: Vorarbeit zu einer Prosopographie der christlichen Kaiserzeit. Stuttgart, 1919.

________. "Das sogenannte Edikte von Mailand." Zeitschrift für Kirchengeschichte. 12(1891): 181ff.

Sordi, M. The Christians and the Roman Empire. Norman, 1994.

Notes

[[1]]ILS 660, 663, 682-684, 687-9, 695, 701, 704, 713, 6787; such variations as Flavius Constantinus(ibid., 694, 697, 699, 702-3, 705) or simply Constantinus(ibid. 664, 681, 685-6, 700, 706-712, 715-6, 6091) appear on inscriptions.[[2]]Barnes has summarized the problems and the sources surrounding the marriage of Constantius and Helena as well as the date of Constantine's birth(Constantine and Eusebius,, [Cambridge, 1981], 3, 286, n. 1, New Empire of Diocletian and Constantine, [Cambridge, 1982], 39-40).

[[3]]Constantine as Galerius' hostage: Zonar., 12.33(PI645A8ff); Constantine's escape to Britain: Lactant., Mort. Pers, 24.2ff; Anon. Vales., 2.2.4; Aur. Vict., Caesar., 40.2, Epit., 41.2; Eutrop., 10.1.3; Paeanius, 10.1.6; Jerome, Chron. ann. 2322(Helm, 228); the date of acclamation: Socrates, Hist. Eccl. 1.2 PG 67, 364Aff; Cons. Con. ann. 306(Mommsen [ed.], Chronica Minora, MGH, AA,, 9.1.231); the Chronicon Paschale only gives the year(ann. 306[1.518.20ff]); description of the acclamation: Pan. Lat. 6(7).8.2; the whole affair seems to have been orchestrated by Crocus, the Alamannic king(Aur. Vict., Epit., 41.3).

[[4]]For a discussion of the chronology of theses emperors' reigns, see Dietmar Kienast, Römische Kaisertabelle: Grundzüge einer römischen Kaiserchronologie, (Darmstadt, 1990), 260ff, and Barnes, New Empire, 3ff; Barnes discussed these civil wars(Constantine and Eusebius, 28ff).

[[5]]For a discussion of the Battle of the Milvian Bridge and the sources that treat it, see Michael DiMaio, Jörn Zeuge, and Natalia Zotov, "Ambiguitas Constantiniana: the Caeleste Signum Dei of Constantine the Great," Byzantion, 58(1989), 333ff.

The dating of Constantine's civil wars against Licinius is a major source of debate among scholars which will probably never be resolved; this is due to the fact that the literary, numismatic, and legal evidence is so ambiguous. It has been traditional to date the civil wars between the two rulers to 314 and 324 respectively, following the magisterial arguments of Otto Seeck(Regesten der Kaiser und Päpste für die Jahre 311 bis 476 N. Chr.: Vorarbeit zu einer Prosopographie der christlichen Kaiserzeit, [Stuttgart, 1919], 162ff; idem., RE 13, s.v."Licinius[31a}," col. 224.36ff). Based primarily on the numismatic evidence, Patrick Bruun has argued that the campaign of 314 actually occurred in 316(Constantinian Coinage of Arelate, [Helsinki, 1953], 17ff; idem., Studies in Constantinian Chronology, [New York, 1961], 10ff; idem., Roman Imperial Coinage 7: Constantine and Licinius A.D. 313-337, [London, 1966]), a position followed by Barnes("Lactantius and Constantine," Journal of Roman Studies, 63[1973], 36ff; idem., Constantine and Eusebius, 65ff, 318ff, and idem., New Empire, 71ff, 81ff). Following the lead of R. Andreotti(Dizinario epigrafico di antichitâ romane 4, s.v."Licinius[Valerius Licinianus]," 1000ff), I and others have argued the evidence makes more sense if the first campaign was actually fought in 314 and 316(Michael DiMaio, Jörn Zeuge, and Jane Bethune, "The Proelium Cibalense et Proelium Campi Ardiensis: The First Civil War of Constantine I and Licinius I," AncW, 21[1990], 87ff). Pohlsander has challenged some of the conclusions of the aforementioned article (Hans A.Pohlsander, "The Date of the Bellum Cibalense: A Reexamination," AncW 25 (1995), 89-101).

[[6]]Barnes, New Empire, 33ff, 43ff.

[[7]]Two accounts of Constantine's vision are preserved; Eusebius says that Constantine and his army saw a cross of light in the sky with the inscription in hoc signo vinces(VC, 1.28ff), whereas Lactantius argues that the emperor had a dream in which he saw the Chi-Rho and was directed to have the signum dei inscribed on his soldiers' shields(Mort. Pers., 44.4-6). I and others, following the lead of F. Heilland("Die Astronomische Deutung der Vision Kaiser Konstantins," in Sondervortrag im Zeiss-Planatarium-Jena, [Jena, 1948], 1ff), have argued that the latter account represents the true course of events because the emperor saw a conjunction of the planets Mars, Saturn, Jupiter, and Venus in the constellations Capricorn and Sagittarius, something which was extremely negative astrologically and would have undermined the morale of Constantine's mainly pagan army. By putting a Christian interpretation on the astronomical event, the emperor converted the sign into a positive force which would be useful to him(DiMaio, Zeuge, Zotov, Byzantion, 58[1988], 341ff).

Star Chart of the Chi-Rho in Constantine's Vision

Star Chart of the Chi-Rho in Constantine's Vision

[[8]]The so-called Edict of Milan is discussed, for example, by O. Seeck, RE 13, col. 222.37ff, idem., "Das sogenannte Edikte von Mailand," Zeitschrift für; Kirchengeschichte;,12(1891, 181ff, DiMaio, Zeuge, and Zotov, Byzantion, 58(1988), 35ff, and, in passing, by Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 318, n. 4.

Harold Mattingly and B.H. Warmington, in brief compass, summarized the religious transformation of the state by noting...

" While ruler of the West only, where paganism was deeply entrenched, he gave much material to the Church and privileges to the clergy. After he had settled in the east where Christians were more numerous his assertion of the new religion became more emphatic. He openly rejected paganism, though without persecuting its adherents, favoured Christians as officials, and welcomed bishops at court. His actions in church matters were, however, his own, and designed soley to maintain the unity of the Christian Church as essential to the unity of the Empire. He failed entirely in the Donatist schism in North Africa...; in the East he called the first general council of the Church in Nicaea in 325 to deal with the Arian controversy, but his apparent success was rapidly viewed to be superficial"(OCD,2 s.v."Constantine," 280).

The transformation of the Roman state from paganism to Christianity is discussed, for example, by Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 44ff, 191ff, 208ff, and B.J. Kidd, A History of the Church to A.D. 461,(Oxford, 1922), 2.5ff.

[[9]]A.H.M. Jones,OCD,2 s.v."Theodosius(2) I," 1056.

[[10]]Pace the views of M. Sordi, who does a fine job of outlining the various positions taken by scholars on the timetable and nature of Constantine's conversion(The Christians and the Roman Empire, [Norman, 1994], 13ff), I and my coauthors have argued that Constantine, the consummate politician that he was, handled the matter very adroitly by using ambiguous symbolism that would not offend either the Christian or pagan factions at his court(Byzantion, 58[1988], 352ff).

For a discussion of the circumstances surrounding the death of Constantine, see infra, n.18.

[[11]]For a discussion of the sources and history of the Council of Nicaea, see Barnes, Constantine and Eusebius, 214ff.

[[12]]Praxagoras of Athens, FHG, 4.2; Julian, Or. 1.8B-C; Sozom., Hist. Eccl. 2.3.2; Zos., 2.30.1ff; Anon. Vales., 6.30; Socrates, Hist. Eccl., 1.16 PG 67, 116Bff; Orosius, 2.28.27; 10.8.1; the foundation of Constantinople is discussed by A. Alföldi. "On the Foundation of Constantinople: A few Notes," JRS, 37(1947), 10ff; Dagron's treatment of the foundation and history of the Queen of Cities is the locus classicus of all discussions of the subject(G. Dagron, Naissance d'une capitale: Constantinople et ses institutions de 330 à 351, [Paris, 1974], 15ff).

The renaming is discussed by Alföldi(JRS, 37[1947], 11) and the date that construction actually started is referenced by me(DiMaio, Zonaras' Account of the Neo-Flavian Emperors, [Ph.D. diss., University of Missouri-Columbia, 1977], 200, n. 1.).

[[13]]Constantine's building program is discussed, for example, by E. Oberhummer, RE 4, s.v."Constantinopolis," col.968.52ff, 975.18ff, 992.8ff,, Alföldi, The Conversion of Constantine and Pagan Rome, (Oxford, 1969), 113ff, and Dagron, 387ff.

For a discussion of the exclusion of paganism from Constantinople. see Mattingly and Warmington, OCD,2 280, and Jones, ibid., s.v."Constantinople," 281.

[[14]]Dedication date of Constantinople: Cons. Con. ann. 330(Mommsen [ed.], Chronica Minora, MGH, AA,, 9.1.233-4); for a fuller listing of sources, see DiMaio, Zeuge, and Zotov, Byzantion, 58(1988), 353, nn. 104-105; Constantine's comments on the foundation of Constantinople: Cod, Theod., 12.5.7, urbis quam aeterno nomine Deo iubente donavimus...

The dedication ceremonies themselves combined both pagan and Christian elements which would not offend either the Christian or pagan cliques at his court(DiMaio, Zeuge, Zotov, Byzantion, 58[1988], 353ff, Mattingly and Warmington, OCD,2 280; Jones, ibid., 281).

Many of the Queen of Cities' political institutions duplicated those of the old Rome(Dagron, 43ff, 120ff, 214ff, 226ff ;Alföldi, The Conversion , 112ff,: Jones, The Later Roman Empire: 284-602, [Norman, 1964], 1081, n.13). The nature of certain institutions, however, clearly indicates that Constantinople initially had a lower status than did Rome(DiMaio, "Zonaras Ecclesiasticus: Three Source Notes on the Epitome Historiarum," GOTR, 25[1980]. 78, 81, nn. 12-18).

[[15]]Julian, Or. 1.8Bff(following the interpretation of Dagron, 34).

[[16]]Zonaras(13.4.29ff), citing Julian as his source(Caes., 335B), notes that the emperor spent money lavishly. This claim is not exaggerated. Constantine looked for opportunities to bestow riches and offices upon his friends(Eutrop., 10.7.2); he often created new offices to enrich some of those around him. In fact, anyone asking the emperor for a favor usually received more than he expected(Euseb., VC 4.1, 1.43). During his Vicennalia, the emperor dispensed large amounts of money to his subjects(ibid,, 3.22). Constantine also alloted large sums for the care of the poor, widows and orphans(ibid,, 1.43), and provided dowries for young women(ibid,, 4.28). It is alleged that he even gave compensation to those who lost their cases in court(ibid,, 4.4). Generous donatives were also given to the army(Julian,Or. 1.8A) and the pagan subjects of the empire(Euseb., VC 2.22).

Harshness of Constantine's taxation: Zos., 2.38.1, 3; Zosimus' statements might be considered excessive, yet Aurelius Victor notes that there was a jingle floating around which portrayed the emperor as a spendthrift(Epit. 41.16).

[[17]]Zos., 2.38.1; Euseb., VC 4.54; Amm. Marc., 16.8.12.

[[18]]P. Franchi De Cavalieri. "Il fumerali ed il sepolchro di Constantino Magno," Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire de l'École Français de Rome, 36(1916-1917), 206ff; DiMaio, "Zonaras, Julian, and Philostorgios on the Death of Constantine I," GOTR, 26(1981), 118ff.

[[19]]For the dates of their births and the sources that treat them, see Barnes, New Empire, 44-45.

[[21]]For a discussion of the demise of Fausta and Crispus, H.A. Pohlsander, "Crispus: Brilliant Career and Tragic End," Historia, 33(1984), 99ff.

[[22]]For a discussion of the purge of 337, the succession of the sons of Constantine, and the sources that treat these matters, see DiMaio and Duane Arnold, "Per Vim, Per Caedem, Per Bellum: A Study of Murder and Ecclesiastical Politics in the Year 337 A.D.," Byzantion, 62(1992), 158ff.

Copyright (C), Michael DiMaio, Jr. This file may be copied on the condition that the entire contents, including the header and this copyright notice, remain intact.

Copyright (C), Michael DiMaio, Jr.. This file may be copied on the condition that the entire contents, including the header and this copyright notice, remain intact.

For more detailed geographical information, please use the DIR/ORBAntique and Medieval Atlas below. Click on the appropriate part of the map below to access large area maps.

DIR Atlas

DIR Atlas